One of the things that quickly becomes apparent after spending more than a day in Kenya is the ubiquity of mobile money.

By this I broadly mean using your mobile phone to pay for stuff, something often cited in the UK and elsewhere as the next generation of money which is “surely going to take off next year”.

Well, in Kenya, it has already. At last count, 43% of GDP flows through the leading provider, M-Pesa.

How does it work?

In simple terms you top up your phone with credit and then transfer it to someone who you want to pay. This could be a friend, utility company, or shop that you walk into. You can also go to an outlet and withdraw your credit as cash.

Whilst this idea of paying for things and taking cash out might sound like a bank, instead M-Pesa is essentially a mobile product. More on that later though.

It is an interaction between the physical and digital worlds so I’ll walk you through how I got started after setting foot in Nairobi.

Getting started

Register with a SIM card

For M-Pesa you need to get a SIM card for a telecommunications company (telco) called Safaricom. I had to show my passport, fill in a form, and there you have it.

Activate M-Pesa

There are some SMSes that need to be sent in order to get it all set up, but this can all be done without an internet connection and if you ask nicely, the man at the counter will do it for you

Top up your M-Pesa account

Next, take cash that you have and go to a little booth/ kiosk (they’re often in a supermarket/ pharmacy/ phone shop) and tell them your number and hand over the money. They’ll make a note of it, press some buttons on their phone and then confirm that you are the person your phone number says you are.

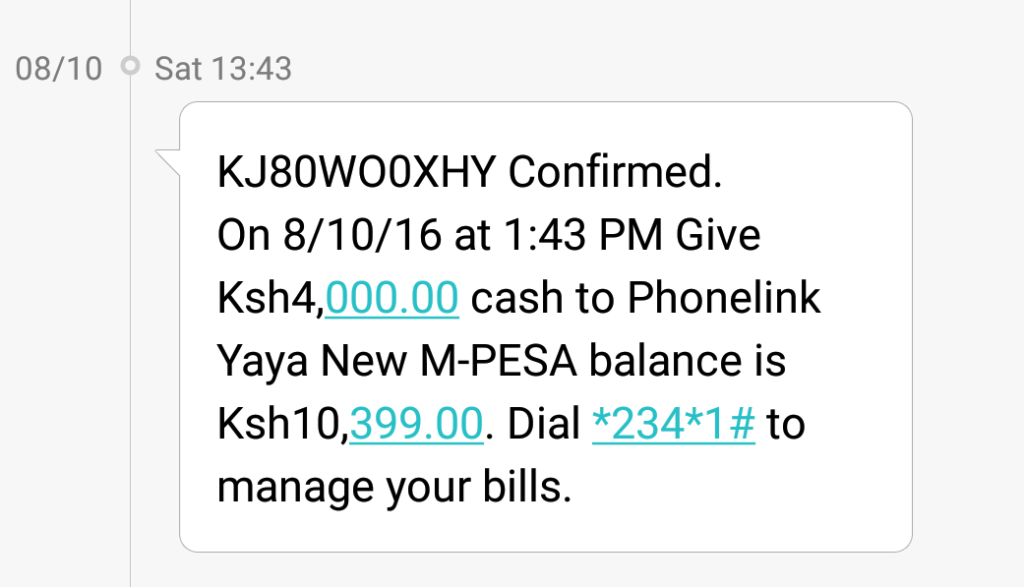

Each party then gets a text message saying your account has been topped up. It looks a little like this.

Both parties show each other their phone screen to confirm that it’s gone through.

Cash out cash in

The thing that at first I found a bit counter-intuitive was finding myself queuing at an ATM to get cash out to then line up in another queue to give it to an M-Pesa teller.

But then I realised that most people don’t have bank accounts that they can withdraw money from, as most of their transactions will occur with cash. This cash needs somewhere to live.

Anyway, for those that need it there is now (of course) an app to transfer money directly from your bank account into your M-Pesa account.

Spending money

Getting money off your phone is where things get even more interesting.

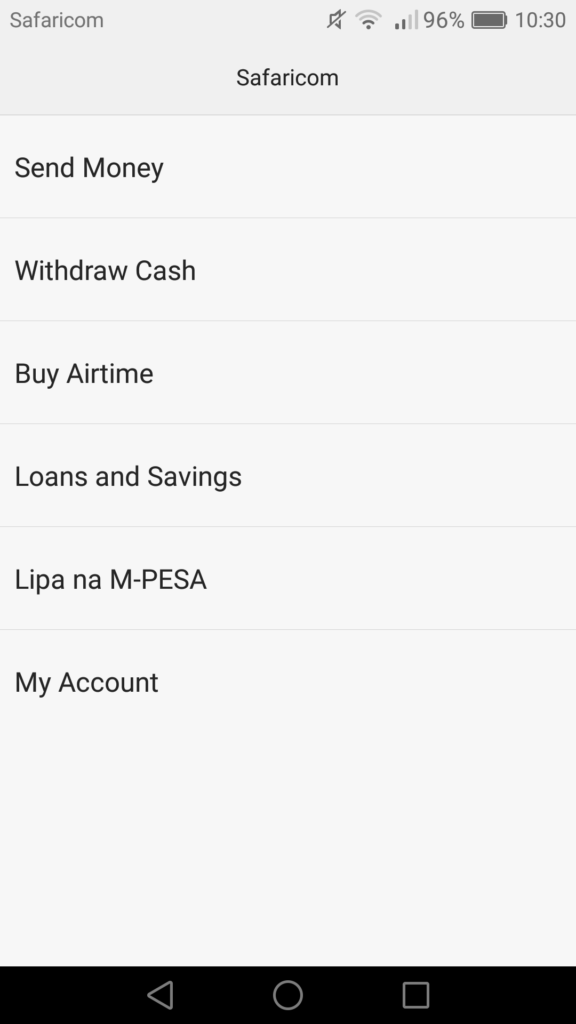

Safaricom has this in-built basic application that works on all mobile phones (i.e. not just smart phones) where you send USSD codes to navigate through menus of what you want to do. It feels like you’re sending an SMS but apparently technologically it’s different.

It’s a bit like those text messages you sometime get which say “text STOP to stop receiving these messages”: the phone only recognises the pre-determined messages.

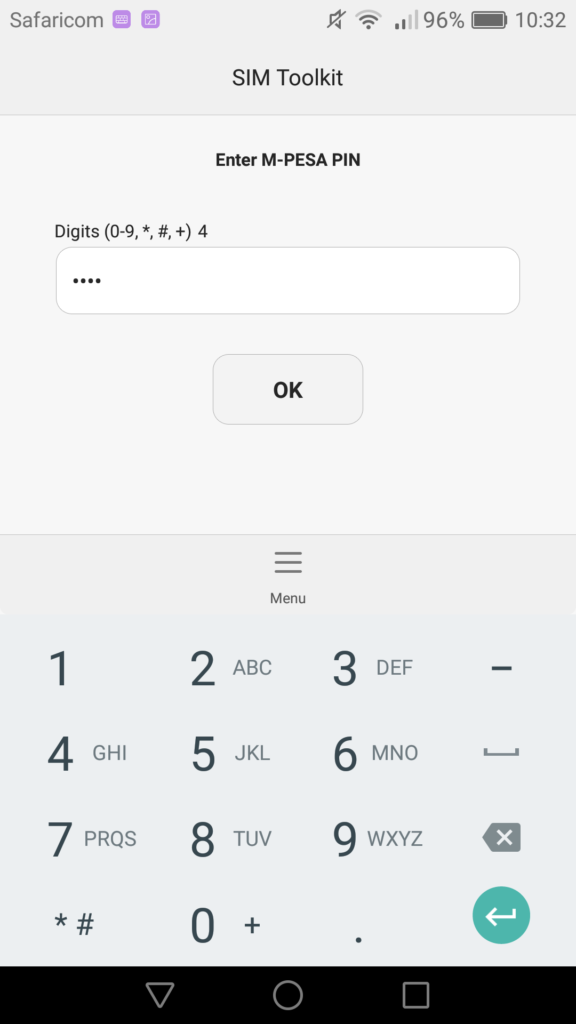

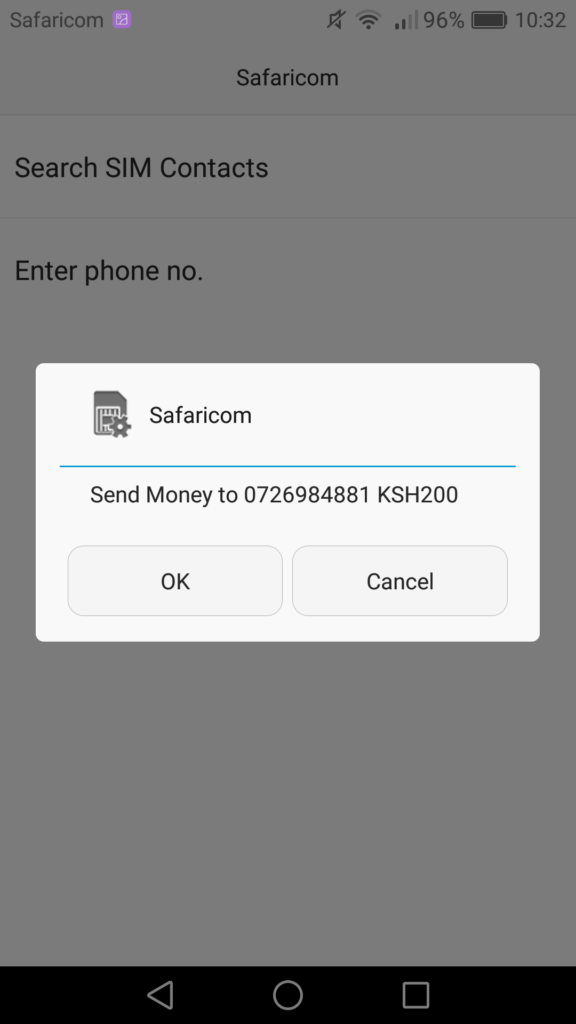

Anyway, from here, stages we’re talking about involve this type of interaction with M-Pesa “app”

To your friend

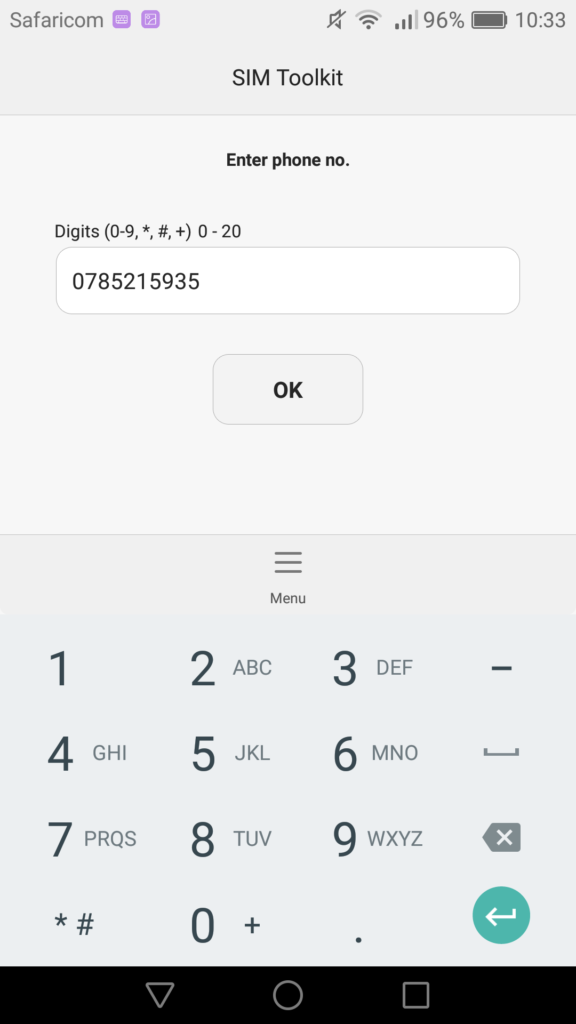

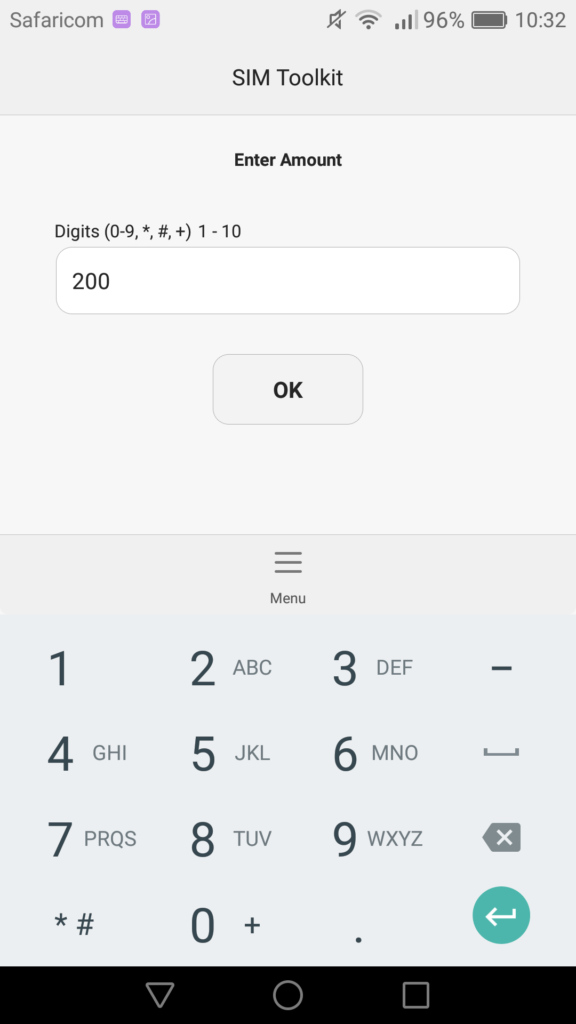

From the main menu you select that you want to send money, and then go through three steps

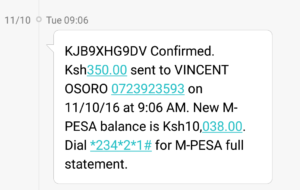

and then confirm it

There’s then a text message sent confirming it all.

I also use the above method when paying for things like motorbike journeys and so even though (despite wrapping my legs around Vincent for 10 minutes or so) I wouldn’t yet class him as a “friend” this is an efficient means for us to do business.

Pay for things

This certainly feels like an evolution of M-Pesa. I can imagine that shops were wanting to get in on the act of people sending them money (especially if they’re in the habit of not having cash) and so rather than treat it like a person who has a phone, instead M-Pesa set up proper shop accounts where retail outlets can accept M-Pesa.

Almost every shop/ cafe you see has signs for it.

It works in a similar fashion of menu navigation, though this time you have a 6-8 digit code to enter, rather than an 11 digit phone number.

Again, you show the cashier the text message to confirm it’s been paid, and off you go.

Withdrawing cash

I don’t find this part of M-Pesa particularly mindblowing, but for people I speak to, it rocks their world.

You can line up and go to one of these outlets and essentially text the person behind the counter some credit and they will give you some cash in exchange.

This early TV advert from M-Pesa explains a bit more.

Loans etc.

As mentioned, the lines are blurred between M-Pesa being a mobile service or a bank.

With time Safaricom have found it both possible and profitable to offer loans to its users (i.e. credit on their account without needing to hand in cash notes) and then have people repay it back.

There’s a fair amount innovation possible here in terms of using the recorded transactions of M-Pesa to generate a credit history to then get access to bigger loans with other banks. This service here offers some more info.

What’s it used for?

Now that we’ve seen how the logistics work with regard to getting money on and off your phone we’ll take a look at some of the uses

Remittance payments

The main commercial use that Safaricom saw for M-Pesa was in aiding remittance.

Remittance basically means sending money home

The idea being that the son or daughter earning bucks in the city (or indeed internationally) can send home money to family who they want to help out. Send a text and then Mama can go to a rural kiosk and withdraw the money to spend on goods.

Lunch

Or indeed anything you buy where the place has a till (I mention lunch because that’s the first transaction I did).

Retailers have an account and, much like a debit card, if you’re in a group they’ll just deduct the M-Pesa amount from the rest of the tab.

Utilities

A number of services have signed up to receive payments in a world where it was difficult to get cash to them.

Kenya Power for example makes it straightforward for people to pay off their electricity bills.

I.O.U.s

Personally, I’ve found it useful paying someone back if they picked up the bill somewhere. You can sort it there and then rather than having to ask for their bank details, log on to your banking app and then go through all the effort of those security checks.

Where did this all come from?

The history of M-Pesa is interesting: originally it was designed as a more efficient way to administer micro-loans.

A team funded by DFID (UK Department for International Development) were tasked with finding a better solution to getting funds to people in remote areas of a country. The additional cost/ inefficiencies around physically sending bundles of cash to people in rural regions meant that the interest rates on these loans needed to be higher.

The idea of remotely sending people airtime on their phones came out on top and Safaricom (a Kenyan telco and subsidiary of UK company Vodafone) were picked as the pilot scheme provider.

Pass it on

On Safaricom it has always been possible to transfer airtime between phones.

After the micro-loan scheme had been in place for a while, the analysts at Safaricom noticed that lots of people were not only receiving the money on their phones, but actively then sending it on to their friends and family.

The pilot finished in 2006 and after deciding to investigate the scenario a little more, the Safaricom execs decided what the hell let’s give it go, and started setting up a network of physical locations where people could exchange the airtime that could be sent to their phones for cold hard cash.

Why has it worked?

General reason

Cash is faff

First and foremost it should be noted that, whilst paper currency is a good medium of exchange (better than trying to find physical goods of comparable value to trade), it’s not great.

There are many costs, such as

- Financial cost of physically producing notes and coins

- Time cost of finding outlets to withdraw it from a safe store

- Security cost of monitoring, storing and transporting wads of it

- Risk of deterioration: if kept under a bed then small animals can nibble at it

and so from a fundamental perspective, there is room for improvement.

Contextual reasons

Interestingly though, these factors are present in almost all societies that have currency that we recognise today. Some other conditions were clearly at play to lead us to a scenario where M-Pesa is the de facto medium of exchange in the country of Kenya.

Safety

Compared to Western Europe and the US, in Kenya there are many more risks to keeping hard cash upon your person or in your house.

Especially in rural areas, there’s a non-zero chance of a rat chewing up this tasty bit of paper that happens to have the President’s face on it, and also (though I don’t have the stats to hand) I can imagine that robbery and petty theft are more common.

Therefore being able to deposit your money somewhere safer is a concern that people wish to solve.

No banks

This safe place where you deposit money and then take it back sounds a lot like a bank, right?

Well, if cash is faff, then setting up a bank is even faffier. You need to have a big sturdy room to store your wealth (gold, notes etc.) and then a ton of other regulation around taking on people’s money and promising to pay it back. This regulation often includes background checks and requiring things like birth certificates which large swathes of the population in Kenya don’t have.

Because of all of these efforts, banks have left people in rural areas on their to do list meaning there were limited options for safe places to keep your bank notes out of harm’s way.

Trust

Despite this potentially unsafe environment, from what I’ve been told, Kenyans benefit from having a decent level of trust between strangers. The idea of handing over a large wad of your material wealth to a random person with a sign above his shop doesn’t seem too out there, meaning that plenty of people were happy undertaking this type of transaction which gets everything set in motion.

Apparently in Nigeria there isn’t the trust that money deposited with a stranger at a street corner kiosk will actually be returned to you by another, and so people think I’ll rather keep my cash in my top pocket thank you very much.

Follow the leader

Safaricom had a dominant position in the Kenyan telco market meaning that if you and your friend were already on the phone network then it would be possible for you to send money to one another.

If someone was using a competitor network they that meant they were not in the cool kid M-Pesa club and so couldn’t receive money. This FOMO led to more and more people switching to Safaricom which (unlike some cliques) only got cooler the more people joined. This phenomenon is often known as a network effect.

Limited regulation

Whilst Safaricom did get Central Bank approval there was limited financial regulation around in 2007 meaning the telco were more or less left to their own devices.

Going out and marketing M-Pesa whilst financial regulators were still concerned with cheques and other antiquities meant that Safaricom could get a massive head start before the powers that be realised that a mobile phone company was doing revolutionary stuff on their turf.

Now the regulators have wised up and telcos in other countries (such as neighbouring Uganda) who have subsequently looked to launch their own versions of mobile money have found many more hoops to jump through which has stunted their ability to get wide coverage of a system.

Slick operations

Credit where its due, apparently Safaricom nailed it when it came to understanding what its customers needed. This article explains the back-end logistics of M-Pesa transactions.

Post election violence

Some commentators have pointed to the events after the 2008 Kenyan elections (when thousands were trapped in slums with no access to money) as a turning point in M-Pesa’s growth. In an unstable environment, the need to remotely send money to relatives was much stronger causing more to get on the system.

If elections weren’t relatively soon after the release of M-Pesa, or not as violent, then perhaps the impetus might not have been as strong. Either way, this “historical accident” has been suggested as a critical milestone in the growth of the service.

It’s relatively cheap

Safaricom is a profit-making company and so it charges for its services.

The tariffs are set whenever money bounces from place to place (current prices here). The short version though is that it costs ~2% to withdraw cash and ~1.5% to transfer between registered users.

Whilst the idea of being charged to move money around might seem odd in a world where you can typically do bank transfers for free, the high cost of alternatives means that its a price worth paying.

Innovative applications

Having an environment where people in a society are very happy to bounce money around and have it all tracked through the Safaricom infrastructure has meant that lots of businesses and projects that existed in theory have been able to give it a whirl.

The key in all of these seems to be that being able to record who has received what, and being able to instantly make people wealthier from hundreds of miles away has opened a whole host of applications which people have been gagging to try.

Here are are my top three

GiveDirectly

This is a non-profit which (as you might have guessed) takes donations and gives them directly to people around the world.

Now, from speaking to my friend Eric, the give part is OK, but organising the directly side is difficult. Until you consider mobile money when it suddenly becomes pretty straightforward.

They are piloting a program of giving people a “Universal Basic Income” which has been talked about in academic circles for a while but is only really testable once you have an efficient means to give people the income. M-Pesa has unlocked this opportunity, and so they are running the pilot in Kenya.

It’s dead interesting, you can read about it here.

Inuka Pap

Again, this looks at reducing the cost of transactions in an environment where people don’t have banks.

The alternative is to deposit cash in a SACCO (rural credit union) and then in your moment of need, ask them to help pay for, say, your hospital fees.

The issue was that co-ordinating this transfer of cash was difficult (often taking a few days) meaning if you needed to pay for a taxi to take your daughter to the hospital, you’re going to keep some tucked away so you can access it immediately.

But, as we’ve learnt, cash in houses risks being lost to hungry rats or thirsty husbands and so it’s quicker, safer and easier to utilise mobile money.

Angaza

(and other services that facilitate giving products on credit).

When you consider most transactions, you go into a shop, pay upfront and walk out with the product. Or, you’ll buy something on credit which essentially means that each month, money is deducted from your bank account until you pay back.

Cash upfront and a bank account are two things that people living in rural Kenya don’t have and so they were excluded from buying useful items such as solar lamps, and other appliances.

Angaza’s innovation comes in allowing manufacturers to offer certain functional goods on credit by being able to remotely “turn off” the product if payments stop. Think of a solar lamp. Someone gets given one and then pays back each week until they own it. If they fall behind then the lamp stops working until the start paying again.

The logistics around tracking these payments in cash would have been prohibitively high, however with M-Pesa it’s much more manageable, and therefore more people can have access to solar lamps.

Conclusion

Seeing an economy functioning on this idea of mobile money that I’ve heard about for a few years has been fascinating, and a real insight into the development of Kenya.

A lot of it makes me wonder whether online payment through things like debit cards will become prevalent in East Africa, and especially Kenya.

Innovation is typically a path dependent evolutionary process based on the environment of a situation. In the UK and US, people had money stored up in bank accounts, and so the natural way to pay for things online was to find an efficient means to route the money from the account to the ecommerce store (through entering your debit card number and CVV).

In Kenya though, the starting point has been different.

The place that the majority of people keep their money is in M-Pesa and so trying to force people to convert over to bank accounts and then get debit cards and then online payment portals to accept debit cards might a long way around rather than just playing the environment.

When people talk about “Africa finding its own way”, I’d say this is one of those scenarios playing out.

Additional reading

I found this post very interesting to research and would like to credit the following articles which helped, and which you can reference if you’re interested in learning more.

This video talks about the story of M-Pesa

The Economist has a good article about why in Kenya

Wikipedia describing M-Pesa