On Saturday I went for lunch with the lady who cleans my apartment and her sister at their home in Kibera: one of the big informal settlements in Nairobi.

The conversations and anecdotes that came from our afternoon were rich with the colour of the lives they’ve both lived, and the families they’re raising. On their permission, I’ve written the below.

How we met

The story of how we came to meet is quite interesting. Asha used to work as a security guard at the building where an ex-tenant of my apartment used to work. She mentioned one day that they were looking for “house help”, and Asha suggested her sister, Salma.

Salma has been coming to our apartment for 3 days a week since, and is absolutely brilliant. Asha has now moved to working on reception at the company. They recently moved office to the same building that I work from and so when I go to see my friends who work there, I always say Hi.

We got talking a while back about cooking and Asha said “Well Sam, you’ll have to come over one day”. We followed up, and on Saturday I was taking a matatu (small bus) to where they stay.

“I’ll see you at the stage”

Kibera is a dense area of roughly 2.5 square kilometres. Within it are neighbourhoods demarcated by the main stops on the matatu routes. In London, you might say “I live in Angel”, here Asha informed me to meet at the Makina stage. “Stage” is the name where motorbike taxis (bodas) congregate, and the main stops where matatus pick people up.

Asha greeted me with her “first born” (a common way to describe the eldest child) and we walked along one of the main roads before turning down an alley to her place.

Asha’s house

Asha is a single Mum with five kids ranging from 8-18. They are currently renting from a lady who owns the house, and renovated it recently adding a few extra rooms. Last year they got a metal roof which was a game changer in terms of stopping leaks when it rained.

The main room has three sofas, there’s a bedroom to the right, a kitchen to the left and then a spare room which houses the laundry. “The roof is leaking so we can’t sleep there til it gets fixed”. The courtyard is where laundry dries and there’s an out house for the toilet/ shower.

The family of six sleep between the main room and the bedroom. Asha is in the bed with her two daughters, and each evening the boys sleep in the living room.

In terms of amenities, they have a ~24-inch TV, bottled water dispenser and fridge. The latter has a magnet from Asha’s work which I couldn’t agree with more.

Salma lives maybe a three minute walk away. She was conscious of me visiting where she stayed, because if her landlord of a white person coming over he’d up the rent…

I spoke with Asha’s three boys for a while first, and then the two daughters came back from school around the time that Auntie Salma brought the food.

What we ate

We agreed that Asha would take care of the side dishes, and I’d bring the main.

Sides were the staples in every Kenyan meal time: ugali (corn flour) and sukuma (kale). I brought along some special recipe beans (secret ingredient: cocoa powder) and a pineapple salsa. Mangoes are out of season, and so I couldn’t do the usual.

The food was heated on the two point gas stove and then the pots were laid on the floor in the living room whilst we dished out portions.

Age dictated whether you sat either on a sofa or the floor, and we used our right hand to squidge up ugali and dip it in the beans. Once we finished, a jug of water and a large bowl were passed around to wash hands: one person pouring for the other.

“Tell me about your family”

This was a rich topic for us to discuss. We exchanged phones so I could show pictures of my family. Asha found this particularly interesting (apparently I have my Mum’s nose) and was slightly perplexed as to why I only had one sibling.

After a probing, I ended up promising her that I would have at least four children which seemed to satisfy her.

When we spoke about their family Asha and Salma began smiling, and reminiscing about growing up.

Their Mum was from Sudan, and Dad from Kisii (in Western Kenya, near Lake Victoria). “I have no idea how they met” Asha said. “They were so different!” chimed in Salma.

The Sudanese, Asha explained, were fierce people. Not very friendly. “And yet my Dad was so happy and friendly?!”.

Asha said: “I wish I asked them how they met.”

There’s was a polygamous family. Their Mum was the third wife of their Dad, meaning they have step-siblings dotted around the place, whom they still go to see. I’m unclear exactly when, but before the age of ten the family had moved to Kibera.

“Let’s take a selfie”

Asha is the more outgoing of the two and when we proposed to take a family pic, she self-nominated as photographer. Salma, by comparison, is much shier, and undertakes a nonplussed glance-away when having her photo taken.

We then said goodbye to the kids and Asha and Salma showed me around where they grew up.

A walk around town

Out of the house was a row of others, and then kids playing in the courtyard. The three of us set out walking and soon found small groups of children congregating behind in fits of hysterics until one would pluck the courage to squeal “Howareyou?”.

A response of “mzuri sana” (very good) would lead to yet more giggles, and then they’d scurry off to wherever they were playing.

There was a bustle on every corner, with each shop specialising in something in particular. There was the egg depot, a guy who’d sharpen knives (handy for butchers), a barber, as well as clothes being strung out.

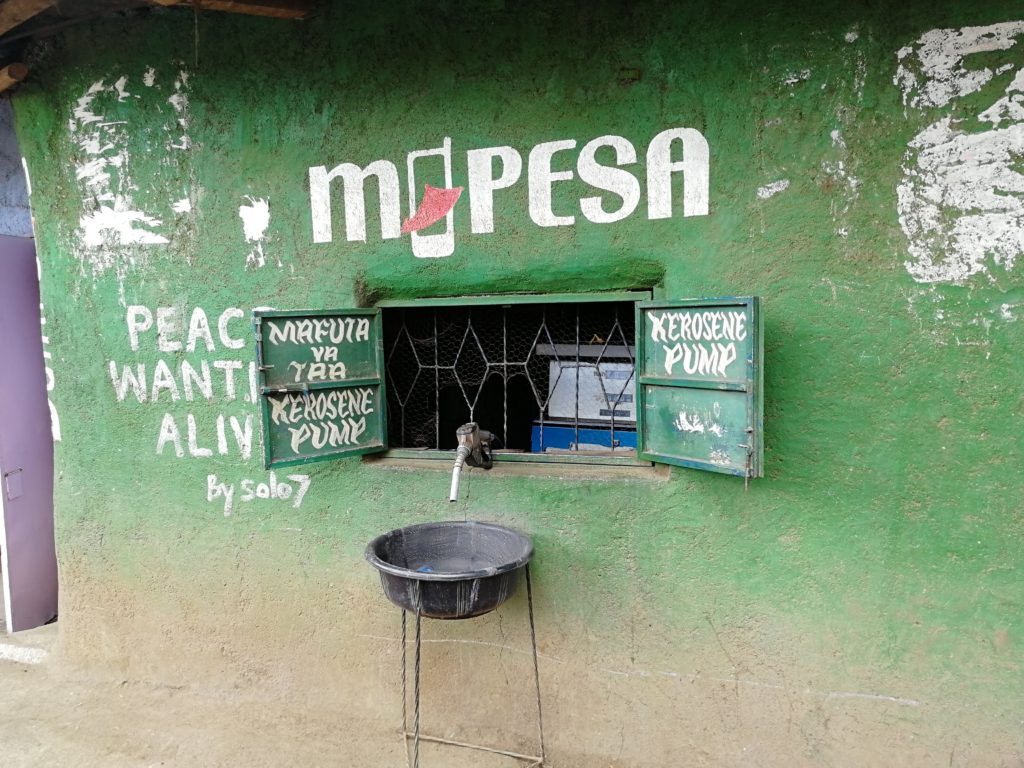

The one shop type I’d not seen previously was a “Kerosene ATM”.

Essentially a petrol pump, people would go to buy small quantities of kerosene to fuel their stoves. A man/ women inside the kiosk would squeeze out the amount for a fee.

“Asha, do you use kerosene to cook?”

“Not any more. With the small kitchen it gave me a really bad chest, now I’ve been able to switch to gas”.

The kiosks serve all of the typical day to day items, but in smaller sizes

Things like toothpaste, soap, and even instant coffee are sold more or less in single servings. When cash is tight to hand, it’s economical to buy just as much as you need and so companies have adapted by creating packages which, on a per gram basis, are much dearer but total outlay is much lower.

Adverts for products were often painted directly on the walls of buildings. This is a common strategy by brands looking to increase exposure – in exchange the person who owns it gets a free paint job, and maybe some cash.

Pasta is one that stood out from the usual telcom and soap adverts.

“Oh yes” Asha said, “pasta has become very popular recently – it’s so easy to cook!”.

We ambled slowly as others got busy with where they were going. At one point we stopped to watch a little kid become fascinated with a kitten.

Asha said how she looked after a neighbour’s kittens once and had her children’s schoolfriends came around almost every evening so they could play with them.

Trip down memory lane

Turning a corner we got to the school where Asha and Salma had attended and then took a left to go down to the railway line.

A train runs from Kibera to “town” (Central Business District) which in the mornings is packed with people going into the city to make a living.

When the train isn’t running it serves as a walking route to bypass the back alleys, and also acts as a boundary with the “deep slum” (as Asha described it). The tracks are lined with litter and shops. The latter sell things like HiFi systems, as well as carpentry workshops for those making furniture.

We went back up to the street level and to some other places where the two of them had grown up.

The maize mill

With ugali (cooked corn flour) being the staple, some families choose to buy their corn, and then have it ground into flour (called unga) rather than buy it packaged.

Most Kenyan communities have what’s called a “posho mill” which is where you come with your corn and can then get it ground into flour. It’s basically a room with a machine that funnels corn in and it comes out as flour.

Back when they were kids Salma apparently convinced Asha that she needed to be the one to go and collect the unga, even though it was a loud and dusty pursuit.

“Can you believe she’d do that Sam?”

In return Salma would be tasked with carrying the jerrycans of water from the depot, and back to the house.

The mosque (and church)

Within the dense area we’d walked around we’d passed several mosques and churches.

Asha apologised for not showing me the mosque they go to, however she couldn’t take me to the male section and her first born (Khalil) had by this point gone to meet some friends in town.

I asked whether there were areas where Christians lived, and Muslims lived somewhere else

“Oh, Muslims, Christians, we all live together”

Growing up Asha said she was very curious about this thing called church, and because that’s where all her friends went on Sundays, she would go there too.

The kids’ schools

Salma also has (three) children who go where Asha’s kids go. Both mothers took pride that the school they were at was one of the top performing in Kibera.

I asked what subjects their kids were good at. Asha said that one of her daughters would probably be an accountant (“whenever we get bread she’s always the one to say how many slices we’re all getting”), Salma said one of her’s really enjoyed English, and another IRS (Islamic Religious Studies).

We talked about school fees. Per student, it costs ~$10/ month to send the kids to school. For the elder ones going to college, this can go up to $270/ semester.

For the kids in primary school each class is 1 teacher: 100 children

Both identified paying for education as one of their top priorities, but that it was tough being single income households.

Back to our homes

We’d now circled back to the main road that went through Kibera and were approaching Makina stage.

I picked up some groceries and then said goodbye to them both under strict instruction that I should call them once I got home (which I duly did).

It was then a 10-15 minute walk in the sunshine passing more bustle of workshops and restaurants. When I got back Asha and I exchanged photos from the day, with a promise to return with friends before too long.