Over the Easter weekend a good friend (Ben) and I spent a couple of nights an hour out of Nairobi. Despite the primary goal of “getting a way from it all”, the short excursion ended up showing several aspects of Kenyan culture not always visible from the day to day:

The Chinese influence, a hangover from the colonial era, and the emerging Kenyan middle class.

Setting the scene

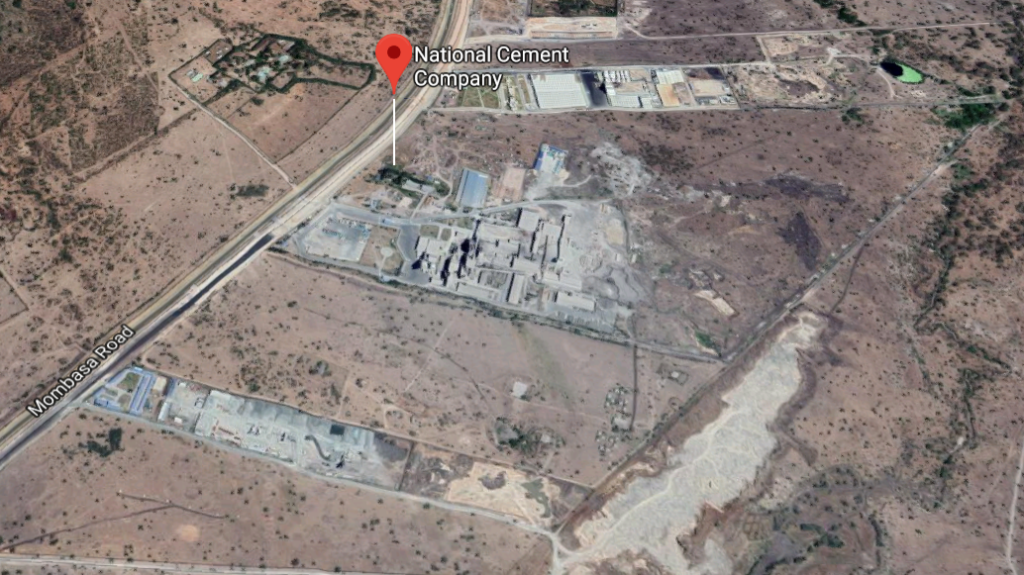

Driving out of Nairobi is the industrial Mombasa Road.

Office blocks and malls become warehouses and small factories as you pass signs for ceramics, furniture and manufacturing inputs.

A mile or so behind them is the boundary to Nairobi National Park: a reserve owned by the Kenyan Wildlife Service that is home to lions, giraffe, zebra etc. It’s the big green patch on the map below.

About 20 miles from the city centre is a town called Athi River: an industrial hub at the apex of routes to the port in Mombasa, and Tanzania. Slightly out of the city, this is home to factories that occupy much more of the landscape.

Every inch of available space along the road is taken up by industrial firms using the prime real estate to produce goods, and efficiently ship them around the country and the world.

And then… green.

Swara Acacia Lodge

Taking a turning just before the gigantic National Cement Company, we drove into a private conservancy.

The place we were staying is called Swara Acacia Lodge, a pocket of solitude amongst a 22,000 acre wildlife reserve owned by a British Kenyan family.

The lodge itself was blissful: little thatched cabins with friendly staff and an abundance of activities. The target market is young families, and so there were all sorts of games and crayons at hand to entertain those who prefer to toddle.

After checking in, Ben and I ordered some lunch and settled into some seats in the garden.

It was here we got our first of three interactions with players on the Kenyan periphery.

1. China

“Ni hao”

I made a simple enough gesture to five middle aged Chinese men also basking in the sun.

The response was animated, asking (I believe) whether I spoke Mandarin, how we were doing, and what we thought of the Italian noodles (spagetti). I had to admit that the two syllables I’d shared with them were the full extent of my Mandarin and so we spoke in broken English.

Jinqing was taking his colleagues out on a day trip. He was in the business of manufacturing plywood for construction and had a factory down the road.

The conversation was all very interesting to his colleagues and after we’d more or less exhausted the extent of what we could communicate one of the elder guys was particular eager to get a picture. As such, myself, the hotel manager and one of the staff were summoned to hold hands and have our picture snapped.

This led to FOMO from the others, and so Ben and duly took turns for the Sino-Kenya Plywood Corporation to each get a pic with us.

The company weren’t staying, and so once they extinguished their cigarettes we said xièxiè (thank you) and bid them farewell.

Key takeaway

How do Chinese and Kenyans communicate?!

Growing up in China it’s no doubt incredibly difficult to learn the new alphabet and nuance that comes with English. These guys were speaking with a native English speaker and it was really tough to have a conversation beyond one word answers and nods.

In Kenya, where despite a good level of English, it’s still the second/ third language that people speak, I’m fascinated by how it’s possible for the two sets of people to interact.

Interestingly, for the railway line built between Nairobi and the coast the Kenyan staff are being trained by the Chinese constructors in ways of customer service: i.e. bowing as a gesture of thanks when people come onboard.

2. Land ownership

The 22,000 acre (i.e. 80 km²) plot has been owned by a Professor (David Hopcraft) whose grandfather had the area since 1904. David bought it in 1963 and has owned it ever since, with about 20 people residing on it, as well as hosting the Swara Acacia Lodge.

It’s a bit like a massive farm, but that there are cheetah, wildebeest, ostrich, giraffe and lots of DLA (deer like animals) roaming around on the plains.

The Hopcrafts live here some of the time: David is a retired conservationist and so it made sense to live amongst your subjects, otherwise the area is driven through by guests at the lodge, and the few other people who call it home.

Lucrative road access

Remember the point earlier about prime real estate on Mombasa Road?

Well, the conservancy borders the road which is currently just grassland up to the edges. Industrial companies would pay a small fortune (~$millions/ acre) to lease the land and so the big debate between the conservancy residents is whether the Hopcrafts should put it up for lease.

Bordering the conservancy is a huge cement factory which dominates the landscape.

One argument could be to retain natural spaces at all costs: once wildlife land is given up, it’s never reclaimed and so it should never be compromised.

The other is that despite the environmental costs, industry is value creation for the economy, and that jobs and infrastructure that could result should be prioritised over 0.01% of a patch of land.

Eccentric habits

On a drive around the conservancy with the hotel manager we saw all but the cheetahs mentioned above. Arriving at one end of the park we unchained the gate to one of the buildings, and inside it was… surreal.

In a dusty garage were 10 or so vintage vehicles.

We’re not just talking a 1980s sedan but prime vehicles from nearly 100 years ago. There was a 1950s Maserati, Cadillacs, two Ford Model Ts, and two Rolls Royces from the 1920s.

I’m not particularly one for cars, but this was really bizarre: seeing museum grade vehicles amidst the savannah.

Apparently it was fairly common for (British) aristocrats to bring out their fancy cars to “the colonies” and so these vehicles were brought over many decades ago and have been here ever since.

Key takeaway

As a British person living in modern day Kenya, I find the concept of land ownership particularly, well, unsettling.

Whilst the law has been followed in terms of British families being converting to Kenyan citizens at the time of independence, and private ownership of land being a remedy to the tragedy of the commons, this his was one of the most striking examples of the inequality that exists in East Africa.

I don’t like talking so overtly about race, but to have 40 people living on miles upon miles of open land when within an hour’s drive 40,000 people live in the same area, it can’t help but feel incongruous, especially as the main demarcation is the colour of their skin.

We won’t dwell on causes/ ramifications/ solutions here, but needless to saw it was the sharpest shock on this matter I’ve had in a while.

3. The emerging middle class

Despite stilted Chinese conversations and wanders through grazing giraffes the majority of time was sat in the grounds of the lodge reading books and playing the occasional game of ping pong.

It was peaceful, but not quiet.

The background noise was that of young children gleefully playing amongst the surroundings, at times coming into confused contact with monkeys jumping down from the trees.

Young (small) families

Swara Acacia Lodge is actively setting up as a destination for young families. The reserve has none of the Big Five which means it’s safe for small ones to roam and freely explore the surrounding nature.

Of the ~20 lodge guests, 80% had young children, but not more than three each.

These were middle class Kenyan families, clearly in professional Nairobi jobs and out for a quick Easter getaway. Working parents had decided to stop at 2/3 children and it was clear from appearance that they were well-heeled and receiving a good education.

At least in these circles, the notion of large (i.e. 6+ children) families seems to be over as the reliance on children as economic agents diminishes, and more investment can be made in a few rather than many. This was discussed in a Ugandan wedding I went to in 2016.

Disposable spend

The next thing to note was that beyond Ben and myself, and a couple of other small groups of expats, the audience was completely Kenyan families.

There is an interesting study showing the purchases that are made as economies develop and incomes rise.

In short, when people get money, they can begin to trade it for time – and there’s a rough sequence of things that they’ll trade for. i.e. school tuition comes before a washing machine which comes before international travel.

Anyway, one of the things on the list is domestic leisure activities.

From a business perspective, the placement of Acacia Lodge as a family-friendly destination is a good position to be in as more and more families enter the bracket of wealth where spending on local travel experiences is in their remit.

Key takeaway

I’m genuinely unsure of the size of “the emerging middle class” in Kenya.

When looking at viable business opportunities, it’s always a case of working backwards from your market size, and despite the promising statistics on Kenyans who are willing and able to spend on higher value products and services, my feeling is that it’s limited (for now at least), to a relatively small concentration in Nairobi.

Hospitality appears to be a good place to be in for the timebeing.

Conclusion

This set out to be a quick update on an interesting weekend, but ended up unbundling some thoughts that, to date, haven’t found a logical place to fit.

Living in the day-to-day in East Africa, it can be difficult to comprehend some of the broader trends at play, and this mini-retreat certainly surfaced particular aspects. I hope you find it thought-provoking.

If you have thoughts/ questions on any of the above, please do drop me line via the Contact page.